Conventional Models of Time and Their Extensions in Science Fiction

An article by Krystian Apartakrystian

INTRODUCTIONAt no time, therefore, hadst Thou not made anything, because Thou hadst made time itself.St. Augustine Confessions, Bk. XI, Ch. xiv, 17 Admittedly, time has puzzled thinkers since the dawn of time as we know it. On the one hand, everybody knows what it is, and most people would agree that they live in time and are always bound and subject to it. On the other hand, few would be able to provide an explanation of what time actually is. This ever-present quality seems to be easily comprehended unconsciously, but somewhat surprisingly difficult to apprehend consciously, as illustrated by the well-known quotation from St. Augustine of Hippo: “What, then, is time? If no one ask of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not” (St. Augustine 1886 (397)). Time has been the interest of philosophers and physicists; remarkably different conceptions of time have surfaced in various cultures and religions all over the world. Some believed time to be one of the fundamental quantities, a primitive that served as a backdrop and a frame of reference for all events, a view developed by Isaac Newton in his seminal work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which lay the groundwork for classical mechanics. Others, like Leibniz, believed time to be part of a conceptual apparatus describing interrelations between events. Time is viewed as cyclical, like in the dharmic religions, or as a linear progression towards an end; according to the concept of time in Christianity, the creation of the world by God marks the beginning of time, with the end of everything (eschaton) as the finish line. Finally, the twentieth century saw the unification of time and space into malleable “spacetime,” a concept constructed by Hermann Minkowski shortly after the development of the theory of special relativity by Albert Einstein. Time is measured, by means of various artifacts, beginning with ancient calendars, largely based on movements of celestial bodies, through sun-clocks, water-clocks, hourglasses and finally the mechanical clocks developed around 14th century A.D. The technological advancements of the twentieth century brought the acutely precise atom clocks. Time is standardized all over the world, with various amendments like leap-years, leap-seconds and Daylight Saving Time used to aid the synchronization. Time has a deep personal and social significance; there are thousands of self-help books and workshops available for those who feel they need to learn to organize their time better, or get the most of however much time they have left. As a significant cultural reality, time has also surfaced in myth and literature. Notably, one relatively recent genre that has often concerned itself with the mechanics of time is science fiction. As many critics have admitted, science fiction, as a genre, is readily recognizable, but not easy to define. In the introduction to the Norton Book of Science Fiction, the renowned author and essayist Ursula K. Le Guin asserts that “Science fiction (…) uses techniques both from the realistic and the fantastic traditions of narrative to tell a story of which a referent, implicit or explicit, is the mind-set, the content, or the mythos of science or technology” (Le Guin 1993: 23). Recalling the opinion of the literary critic Brian Attebery, she goes on to state that “(…) science fiction uses science as its ‘megatext.’ The nourishing medium, the origin of the imagery, the motive of the narrative, is to be found in the contents, assumptions, and world view of modern science and technology” (ibid.). The term “science fiction” is a transformation of the term “scientifiction,” coined around the year 1910 by Hugo Gernsback. Gernsback published scientific magazines since the early 1900s. As a means of the promotion of science, the magazines frequently contained stories which were written so as to portray and elucidate the ideas of science in a more appealing way than did the usual popular science texts of the time. The term “scientifiction” preliminarily referred to these stories. However, the first issue of the most seminal magazine in the early history of science fiction, Amazing Stories (also edited by Gernsback), contained literary texts which were significantly more similar to what is termed “science fiction” in the present day. The first issue, dated April 1926, was filled with pieces by the forefathers of the genre, namely Jules Verne, Edgar Allan Poe, Edgar Rice Burroughs and H.G. Wells. And it is in the novel The Chronic Argonauts by H.G. Wells, published as early as 1888, that we find one of the first noted occurrences of the use of imagined technology which allows time-travel. The novel portrays an inventor who uses a “time machine” to escape an angry mob bent on lynching him for “witchery.” The idea of the contraption that allows its user to travel in time was later developed in the well-known book The Time Machine (1895) by the same author. Considered as a classic example of early science-fiction, the novel substantiates the claim that time-travel (and other types of alternation of the usual progress through the time-space continuum) is a theme present in science fiction from the very beginning of the genre. As the ideas and techniques of science fiction progressed, the extrapolative nature of the literature in question generated numerous original storylines, which twisted the commonly held conceptions of the realities of time, and incorporated the advances in science that the twentieth century provided on the way, such as quantum mechanics or computer-generated virtual realities. Most of the most respected science-fiction writers have penned some time-travel literature. With gradual suffusion of sci-fi cinema with the theme of time-travel, the concept of traveling though time has entered the general public’s collective mind. Most people, especially in the occidental cultures, would be able to tell what it means to go back in time, what happens when time is accelerated, and why it would be advisable to avoid contact with one’s direct ancestors while on a trip to the past. There is an interesting question connected with this general knowledge of the rules of time-travel. Time as such has been tackled by physics and philosophy, but few philosophers or physicists have theorized on the possibility of time-travel as it is depicted in science fiction.1 All the existing theories of time-travel notwithstanding, one cannot assume that the science-fiction reader, or the cinema audience, have the theoretical knowledge needed to comprehend those abstruse theoretical constructs. Moreover, it is not the case that science fiction literature or film provides scientifically sound models of time-travel. The hallmark feature of science fiction is that the literature will use scientific discourse to make the scientific content of the story or novel plausible, yet the actual science is in most cases sketchy and simply phony. It is important to point out that physics, the science that time-travel science fiction bases its argument on, originated in philosophy. Philosophical inquiry may be seen as an attempt to provide answers to common questions that would go beyond the commonly available explanations. These questions arose in the human mind’s endeavor to comprehend its natural milieu. I will claim, therefore, that the reason why science-fiction discourse is readily apprehended even by the layman is that it taps into the same processes of everyday inner inquiry and comprehension that physics attempts to provide scientific answers to. The significant goal of scientific discourse in science fiction is not to refer the reader to her understanding of physical theory, but rather to use elements of physical theory to temporarily re-structure the reader’s comprehension of the world and the rules governing it, so that a novel, extrapolated understanding is produced and employed as the science-fiction element of the story. Though scientific terminology and scientific discourse must be there to make the argument plausible enough and make the reader accept the re-structuring of her rationality (at least while she is reading the story), what is aimed at is twisting the reader’s commonplace knowledge of the world. In other words, I claim that successfully written science-fiction will trick the reader into temporarily extending the conceptual representation of the things and relations in the world that she has formed in functioning in a cultural reality, so as to include new “rules,” like those that govern time-travel in the science-fiction text. If this is so, then in investigating a science fiction text one needs to be able to account for both the commonplace representation of the world in the reader’s mind, and for how the writer can “re-structure” that representation for the purpose of involving the reader in the understanding of the science-fiction storyline. In the case of time-travel science fiction, such an account would specifically have to include an analysis of the conceptual representations of time, and all that time concerns, e.g. the temporality of events and causation. Accordingly, in my analysis of time-travel science fiction, I decided to employ the theoretical apparatus provided by cognitive linguistics, as it felicitously serves both the requirements very well. “Cognitive linguistics” is a term referring to a relatively recent tradition of the study of the mind, in relation to language and human social behavior. It arose in the 1970s (initially in a reaction against certain formal approaches to language), partaking of various cognitive sciences, to eventually become one of the most powerful and sophisticated movements in the study of mind. In an overview of cognitive linguistics, Bergen and colleagues describe the two major commitments that the cognitive linguistics enterprise can be characterized by, which are “The Generalization Commitment” and the “Cognitive Commitment” (Bergen et al. 2006: 3-7). As much as the former can be seen as common to all sciences (consisting in the commitment for the science to arrive at generalizing principles, here concerning language), the latter is pertinent to the matter at hand, namely, to the presentation of the commonplace conceptual structure of the human mind. The Cognitive Commitment “(…) represents the view that principles of linguistic structure should reflect what is known about human cognition from the other cognitive and brain sciences, particularly psychology, artificial intelligence, cognitive neuroscience, and philosophy" (Bergen et al. 2006: 6). In trying to meet the two commitments, cognitive linguistics has developed two major areas of research, cognitive grammar and cognitive semantics. Cognitive grammar, notably in the works of Ronald Langacker, attempts to study linguistic organization in relation to general principles of cognition, and sees linguistic structure as motivated by the structure of conceptualization, as researched by cognitive semantics. Other related traditions in this field of study form the group of theories collectively referred to as “construction grammars,” in which grammar is seen as an inventory of constructions, described as pairings of form and conceptual content, which is made up by the conceptual structures described by cognitive semantics. Although the field of cognitive semantics is vast and includes research in many facets of the conceptual content and processing of the human mind, one can enumerate four guiding principles of cognitive semantics. These are: 1) Conceptual structure is embodied 2) Semantic structure is conceptual structure 3) Meaning representation is encyclopedic 4) Meaning construction is conceptualization (Adapted from Bergen et al. 2006: 9) The major theories within cognitive semantics include image schema theory (as presented in Johnson 1987), Idealized Cognitive Models (developed in Lakoff 1987), research into category structure, cognitive lexical semantics, conceptual metaphor theory and theories of metonymy, and theories of mental spaces and conceptual blending. In this thesis, I will provide a description of commonplace knowledge structures concerning time, as researched by cognitive linguistics. Then, I will use those cognitive-linguistic theoretical accounts of time in an analysis of selected examples of time-travel in science fiction, and I will endeavor to provide an account of how the commonplace models are re-structured in the formation of novel, extended models of time. As the tool of analysis I will be using the theories of cognitive linguistics, notably the theory of conceptual blending. In the first chapter, I will start out with an overview of Conceptual Metaphor Theory, as well as provide a description of basic (metaphorical) models of TIME basing my account mainly on Lakoff and Johnson 1999. Chapter 2 presents an overview of mental space theory and conceptual integration theory (also known as “conceptual blending theory”), as well as a conceptual blending account of the structure of the conventional models of time discussed in Chapter 1. In Chapter 3, I will begin by describing the role of episodic memory and the conventional models of LOCATION in the formation of the novel extensions of conventional models of TIME presented in science fiction literature. Then, I will describe several types of extensions of conventional models of TIME that can be found in science fiction, as well as delineate the extensions of conventional models of CAUSATION typical of most time-travel scenarios found in time-travel science fiction. Importantly, most time-travel science fiction foregrounds the effects that the unconventional scenarios of movement in time that the author concocts have on conventional theories of CAUSATION (see Flynn 2003, Rye 1997, Turtledove 2005). Since Chapter 3 endeavors to address the extensions of the conventional models of TIME, and specifically, to provide an analysis of the extensions of the conventional models of MOVEMENT IN TIME in relation to conventional models of LOCATION and conventional models of SELF, as researched by cognitive semantics, the source texts which provided the examples analyzed in sections 3.3 and 3.3 below have been chosen for their suitability for the purpose of presenting the extensions of the models of TIME in relation to the models of (NATURAL) LOCATION2 and SELF. However, since most time-travel science fiction explores the extensions of conventional theories of CAUSATION in great detail, and those extensions are conditioned by and related to the extensions of the conventional models of TIME that the story suggests, I will devote the final section of Chapter 3 to the discussion of selected extensions of conventional theories of CAUSATION in time-travel science fiction. The models of TIME discussed below are probably present in many cultures of the world (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 150). However, considering that the cognitive linguistic accounts of conventional models of TIME referred to below cite generalizations concerning the use of language by native speakers of English, I will assume, for the sake of clarity, that the models of TIME presented below are characteristic of English-speaking cultures, and that the authors of the source texts, as well as the potential readers forming the potential conceptualizations activated in the reading of the English-language source texts which provided the examples discussed below, are speakers of English, and are in command of the conventional models of TIME discussed below. See section 3.3.1.4 below for the discussion of the notion of natural locations of the SELF. Obviously, this assumption warrants further discussion, e.g. an account of the criteria which would allow the categorization of an individual as a speaker of English. However, such a discussion would fall out of the scope of this thesis. See Lakoff 1992 for the overview of the sources for the evidence of the existence and structure of a system of conventional conceptual metaphors for the users of the English language. CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTUAL METAPHOR THEORY AND METAPHORICAL MODELS OF TIME1.1. Overview and basic terminologyIn this chapter, I will present an outline of conceptual metaphor theory, as well as provide an overview of the conventional metaphorical models of TIME.Research into conceptual metaphor began in the seventies, with the paper by Michael Reddy entitled “The Conduit Metaphor” (1979) often cited as the ground-breaking work. The theory was developed soundly in the 1980 book Metaphors We Live By (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), and improved upon over the years, with many publications and a growing number of possible applications, in fields such as literary analysis, politics and social issues, psychology, mathematics, cognitive linguistics and philosophy (see the afterword to the 2003 edition of Metaphors We Live By for a more detailed account of the development of Conceptual Metaphor Theory). Conceptual metaphor, unlike metaphor in the traditional “literary” sense, is seen not merely as a phenomenon of language, but as an overarching phenomenon of understanding. Conceptual metaphor can be defined as “(a conventionalized) mapping between two conceptual domains,” in which the stored conceptual representation of one cognitive model is used to provide a structured understanding of another, instilling the target conceptual domain with, among other things, selected elements, relations, patterns of inference, and axiological content of the source domain. A well-researched example of a conceptual metaphor is LIFE IS A JOURNEY4. This metaphor consists in a mapping of selected aspects of the stored knowledge of journeys onto the diffuse array of stored experience that, as an effect of the mapping, will be apprehended as “life.” This is not to suggest that “life” has a literal, or objective, conceptually represented structure, to which some parts of the culturally learned knowledge of journeys will be applied. Rather, it is in the mapping of the more easily apprehensible array of the remembered experience of physical journeys onto a more diffuse and abstract set of cognitive representations, later referred to as “life,” that the structure of the concept of LIFE is created and apprehended. In other words, the process of conceptual metaphorical mapping creates a gestalt, a knowledge structure intuitively easier for human beings to manipulate and to use in reasoning. As such, conceptual metaphor is an indispensable and ever-present process of thought, underscoring all facets of human cultural behavior, including, but not limited to, the comprehension and production of language structures. A cross-domain mapping like LIFE IS A JOURNEY sets up ontological correspondences between elements of the conceptual substrate of the cultural model of A JOURNEY and whatever structure there is in the stored cognitive representations of “life.” In Lakoff and Turner 1989 the authors, providing an overview of the particular conceptual metaphor in question, assert that the knowledge structure referred to as “journey” calls up a conceptual representation that has a number of differentiated components, like a traveler on the journey, the destination, possible impediments to progress, etc. That knowledge structure, however, must be skeletal enough for the conceptualizer to be able to apply it in the comprehension of something as a “journey.” In other words, it must be possible to apply it to any number of conceptual structures that it is cognitively useful to conceptualize as “a journey.” Lakoff and Turner term such knowledge representation structured in skeletal form a “schema,” and add the term “slot,” used for the elements of the schema that can be filled in. In their description of the internal structure of conceptual metaphors, they state that each conceptual metaphor consists of: slots, mapped from slots in the source schema onto slots in the target, and the mapping of relations, properties and knowledge of the source domain into the target domain. Such mapping allows us to draw inferences about the target domain, which will be conditioned by the inferences entailed by the source domain schema. For example, in LIFE IS A JOURNEY, the “traveler” slot will be mapped onto the person leading the life. The relation in the source domain of journeys, wherein a traveler reaches a destination, will be mapped onto the person leading the life reaching a purpose in life. The properties of possible strengths and weaknesses of the traveler in the journey domain will be mapped onto properties of people leading lives (so that a person can be understood as having some strengths for conducting life, or not being strong enough to move on). Finally, the source-domain inference that when the traveler hits a dead end she cannot continue on the same path will be mapped onto the domain of life, yielding the inference that if the person leading a life has hit a dead end, she must choose a different path, or otherwise she will not be able to “get on” with her life. The most culturally prominent conceptual metaphors are those that are basic and conventional. Lakoff and Turner define the basicity of a conceptual metaphor as the degree to which it is cognitively indispensable in a culture (1989: 56). For example, the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY is a basic metaphor in the English-speaking culture, as it would require extreme effort, or would perhaps be impossible, for a person brought up in that culture to think of life as something other than a forward progression. However, the conceptual metaphor LIFE IS SLEEP is not as culturally prominent, and as such, perhaps, not as basic as LIFE IS A JOURNEY. Lakoff and Turner define the conventionality of a conceptual metaphor as “(…) the extent [to which a conceptual metaphor] is automatic, effortless, and generally established as a mode of thought among members of a linguistic community” (1989: 55). The conventionality of a metaphor is thus a scalar dimension. 1.1.1. Novel metaphorsAnother distinction that Lakoff and Turner posit is the one between a general, conventional metaphor, and a novel metaphorical mapping. Lakoff and Turner state that general conceptual metaphors are not the unique creation of individual conceptualizers, but “are rather part of the way members of a culture have of conceptualizing their experience” (1989: 9). In their discussion of novel poetic metaphors, the authors provide an analysis the creation of unique, non-conventional conceptual metaphors. One process that gives rise to such novel conceptual metaphors is extension. In a conventional cross-domain mapping, certain slots in the source schema are mapped onto existing slots in the target schema, and at the same time, certain mappings can create slots in the target that were not there before. For example, in LIFE IS A JOURNEY, the traveler slot in the source schema of a journey is mapped onto the already existing slot of a person leading a life in the domain of life. However, the path slot in the journey schema is created in the domain of life in the mapping, and in effect, the conceptual structure of the domain of life is organized so as to have a “course of life” slot.Accordingly, new inferences begin to hold for the domain of life, like the fact that in life, one can either move back, stay put, move on, or choose a different path. This, however, is the conventional mapping. An extension, as described in Lakoff and Turner 1989 (67 et passim), creates a new slot in the target, one that the conventional mapping does not presuppose. As an example, consider the title of the fictional journal of a college student: “Speeding through life on the purple chariot” (Example 1). In a possible interpretation of this title, the additional slots of “manner of movement” and “vehicle used in traveling” are mapped from the domain of journeys into the domain of life. This mapping is novel in itself, but readily understood, as it extends a well-known, conventionalized metaphor with conceptual substrate from its conventionalized source domain schema. Another process that holds in the creation of novel metaphorical mappings is what Lakoff and Turner term “elaboration.” In this mental operation, an already existing slot in the conventional metaphor is filled in a non-conventional way. For example, in the expression “life in the fast lane,” the already existent “path” slot in the conceptual metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY is filled with the conventional image of a highway.5 Yet another process that creative conceptualizers have at their disposal is “questioning,” where the boundaries of a conventional metaphor are put into question (for example, in an attempt to show that the metaphor is inadequate). In one of the examples of questioning, Lakoff and Turner quote the following lines by Catullus: Suns set and return again, but when our brief light goes out, there’s one perpetual night to sleep through. Here, the poet is questioning the metaphor A LIFETIME IS A DAY to point out that unlike with the continual progression of night and day in the source domain schema, in what the target domain is a representation of, no day comes after the night. Finally, the creation of a novel metaphorical understanding can be effected by the process known as “composition,” where a composite conceptual metaphor is formed by the conjoint use of more than one conventional cross-domain mapping culturally available for the conceptualization of a given target domain. For example, an article in the San Francisco Chronicle uses the metaphors LIFE IS A JOURNEY and LIFE IS BONDAGE in conjunction to drive a point home (Example 2). The article is entitled “The folly of trying to escape life,” which activates the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY. However, the author states that even when we do escape, “[we] also have to run away to something” (ibid.) providing a completion of the metaphor LIFE IS BONDAGE with LIFE IS A JOURNEY, so as to give the reader an opportunity to achieve new insight into the conceptual domain of LIFE. 1.1.2. Simultaneous mappings and “duals”Two more aspects of the structure of conceptual metaphors need to be addressed. The first one is the prevalence of simultaneous mappings (as discussed in Lakoff 1992). In discussing simultaneous mappings, Lakoff provides a quotation from a poem by Dylan Thomas: “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Lakoff reflects that in its comprehension, the sentence activates the conventional metaphors DEATH IS DEPARTURE, LIFE IS A STRUGGLE and A LIFETIME IS A DAY. All these conceptual metaphors are necessary in forming a conceptualization of the meaning of that line. Similarly, a metaphor like LOVE IS A JOURNEY entails the activation of additional metaphorical concepts, like LOVE IS A PURPOSEFUL ACTIVITY.What is more, one can observe a duality in certain metaphorical mappings, referred to as “duals”. In his discussion of the conceptual metaphor TIME PASSING IS MOTION (Lakoff 1992), Lakoff notes that this metaphor has two special cases, namely TIME PASSING IS MOTION OF AN OBJECT and TIME PASSING IS MOTION OVER A LANDSCAPE. This can be seen as a figure-ground reversal, where in the first special case the TIME PASSING is the figure, and in the second the moving agent implicit in the metaphor TIME PASSING IS MOTION OVER A LANDSCAPE becomes the figure against the ground of the LANDSCAPE OF TIME (see the discussion of these metaphors in section 1.2.2. below). Such a pairing of metaphors based on a figure-ground reversal is referred to as a “dual,” and is by no means an isolated phenomenon in the conceptual system of the human mind (see e.g. the discussion of the duality of the Event Structure Metaphor in Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 194-201 et seq.). 1.1.3 Image schemas and the Invariance PrincipleLakoff and Turner, in describing the power of conceptual metaphor, list “the power of reason” as one of the sources of the great potential of cross-domain mappings (1989: 65). The power of reason is understood as the fact that conceptual metaphors provide patterns of inference to use in reasoning about a target domain. These patterns of inference are conditioned by what structure of the source domain schema is selected for the mapping. What is crucial is that the structure of the source domain schema and its entailments are also constrained, due to the “invariance principle.”In his 1992 essay, George Lakoff defines the Invariance Principle in the following way: “Metaphorical mappings preserve the cognitive topology (that is, the image-schema structure) of the source domain, in a way consistent with the inherent structure of the target domain.” Image-schema theory was developed in Johnson 1987. Bergen and colleagues state that image schemas are “rudimentary concepts like CONTACT, CONTAINER and BALANCE, which are meaningful because they derive from and are linked to human pre-conceptual experience” (2006: 14). Other such rudimentary concepts include PATH, FORCE, CENTER-PERIPHERY, or CYCLE (see Johnson 1987: 28, 42-48, 124-125, and 119-121, respectively). These concepts emerge in our sensorimotor experience and the embodied interaction with the environment, and lie at the basis of ontological metaphors, defined in as “ways of viewing events, activities, emotions (…) as entities or substances” (Lakoff and Johnson 1980: 25). Lakoff and Johnson state that these conceptual metaphors serve a number of functions, e.g. they enable referring and quantifying (1980: 27). Image schemas (like the VERTICALITY or CONTAINER schema) also allow the formation of orientational metaphors, like MORE IS UP or SAD IS DOWN (see Lakoff and Johnson 1980 14-21 et passim). These mappings, indispensable in rational thought, relate whole systems of concepts with each other, and rely on the structure of image schemas (ibid.). In their account of how the invariance principle retains crucial topology in cross-domain mappings and conditions the entailments of conceptual metaphors, Lakoff and Turner introduce the distinction between generic-level and specific-level metaphors (1989: 80-83 et passim). A specific-level metaphor consists of “a certain lists of slots in the [source] schema that maps in exactly one way onto a corresponding list of slots in the [target] schema” (ibid.: 80). A generic-level cross-domain mapping, on the other hand, consists in “not a list of fixed correspondences but rather in higher-order constraints on what is an appropriate mapping and what is not” (ibid.). An example of a specific-level metaphor is LIFE IS A JOURNEY (see section 1.1 above). This mapping consists of two fixed source and target domains (the domain of journeys and the domain of life, respectively), and a fixed list of mappings, whereby the “traveler” slot in the “journey” schema is mapped onto the “person leading the life” slot in the “life schema,” the “distance covered” is mapped onto the “forward progress achieved” in the domain of “life,” etc. A basic generic-level metaphor like STATES ARE LOCATIONS, on the other hand, does not include fixed source and target domains, and instead of a list of fixed mappings, it only provides a list of generic-level constraints on what mappings can be activated between two conceptual domains structured by the mapping of the generic-schema of a STATE onto the generic-level schema of LOCATION. Lakoff and Turner state that “generic-level metaphors relate generic level schemas,” and provide a list of what knowledge structures a generic-level schema contains. These are: - basic ontological categories (entity, state, event, action, situation, etc) - aspects of beings (attributes, behavior, etc) - event shape (instantaneous or extended, single or repeated, completed or open-ended, cyclic or not cyclic, etc) - causal relations (enabling, resulting in, creating, destroying, etc) - image-schemas (bounded regions, paths, forces, links, etc) - modalities (ability, necessity, possibility, obligation, etc) (1989: 81). They also declare that due to the principle of preserving generic-level structure in the mapping, each specific-level schema will preserve such generic-level structure, as well as exhibit additional, specific-level structure. The principle of preserving generic-level structure is defined as follows: 1) Preserve the generic-level of the target except for what the metaphor exists explicitly to change 2) Import as much of the generic-level structure of the source as is consistent with the first condition. (Lakoff and Turner 1989: 82) This is in keeping with what Lakoff describes as the Invariance Principle (Lakoff 1992). The Invariance Principle “ensures” that in cross-domain mapping the generic-level topology will be preserved, so that, for example, an element that is characterized in its generic-level structure by the CONTAINER schema will map onto an target-domain slot that is also structured by the same image-schema in its generic-level structure. This ensures that a concept’s entailments, conditioned by its generic-level structure, will be preserved in the mapping, under the condition that the only inference patterns which will be inherited in cross-domain mapping will be those constrained by the generic-level structure of the slots selected for the mapping. For example, one important element of the generic-level structure of the source domain for the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY is the PATH schema. One of the ways we can see conceptual metaphor at work is the way that its patterns of inference constrain certain linguistic expressions, and make certain other expressions ungrammatical or incomprehensible. Although a PATH is not inherently directional, directionality is often imposed onto it, together with a start and an end point, and an agent moving on the path towards the end (see the discussion of the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema in Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 32-34 et passim, where the entity moving along the PATH is referred to as the trajector). The agent, in turn, prototypically exhibits a front-back orientation, with the agent’s front being directed in the direction of movement, that is, towards the end point of the PATH. Thus, although a sentence like “You have a long way ahead of you” (meaning “there is much work or time to be devoted to the reaching of a certain goal”) will be perceived as grammatical, the sentence “You have a long way behind you” will not probably activate a similar conceptualization in the same context, and will most probably be perceived as very odd, if it is intended to be read as “there is much work or time to be devoted to the reaching of a certain goal.” This is because the sentence “You have a long way behind you” (with the intended reading specified above) does not meet the inference, conditioned by the PATH schema in the generic-level structure of the domain of journeys, that when a location on a path is situated towards the end of the path, and the agent moving along the path has not yet reached that location, that location is conceptualized as being “in front of” and not “behind” the moving agent. What can also be observed are the so-called inheritance hierarchies of conceptual metaphors. That is, cross-domain mappings sometimes partake of and are conditioned by more generic conceptual metaphors, exhibiting something of a hierarchical organization. For example (as analyzed in Lakoff 1992), the structure of the specific-level metaphor LOVE IS A JOURNEY is in a large degree inherited from the more generic metaphor (A PURPOSEFUL) LIFE IS A JOURNEY, which is in turned conditioned by the inferences in the still more generic metaphor LONG-TERM PURPOSEFUL ACTIVITY IS A JOURNEY, which in turn inherits its generic-level structure from the Event Structure Metaphor (see Lakoff and Johnson 178-206 et passim, and 2.4.2 below). 1.2. Metaphorical models of TIME1.2.1 The origins of the experience of temporalityIn Philosophy in the Flesh (Lakoff and Johnson 1999), Lakoff and Johnson introduce the distinction between primary and complex metaphors. The theory of primary metaphors was developed by Joseph Grady in his Ph.D. dissertation (1997). According to Grady, each “complex” metaphor (like LIFE IS A JOURNEY) is made of up primary metaphors (compare the distinction between generic and specific-level mappings, discussed in section 1.1.1 above). A primary metaphor is held to be culturally universal, and its source and target domains are equally basic. These primary cross-domain mappings arise due to recurrent correlations in experience, a process referred to as “conflation” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 46 et seq.). In conflation, “subjective (nonsensorimotor) experiences and judgments” and sensorimotor experiences are regularly associated, so that, for example, the experience of affection is often associated with the sensorimotor experience of warmth. In a later period of development of the individual, the child begins to be able to differentiate between those two domains of experience, but the associations developed earlier persist. Due to this process, the various domains of experience can later be co-activated, giving rise to primary metaphorical mappings, like AFFECTION IS WARMTH.One of the examples of primary metaphors that Lakoff and Johnson provide is TIME IS MOTION (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 52). In this conceptual metaphor, the sensorimotor domain is motion, and the “subjective judgment” component is the passage of time. Trying to provide an account of the origins of the subjective, phenomenological experience of the flow of time, Evans claims that “(…) what makes time inherently temporal is duration” (2002: 17). Additionally, Evans develops an analysis of how the experience of duration arises from certain features of perceptual processing. Perceptual information from many modalities is integrated by virtue of synchronized oscillations of selected neuronal assemblies. These oscillations last for short periods of time, and each such “period” (termed perceptual moment) is bound by a silent interval. Evans suggests that these synchronized firings of neurons enable the formation of coherent percepts (2002: 18 et seq.). Bound by recurring temporal intervals which create perceptual moments, perception seems then to be inherently temporal. According to Evans, the experience of the succession of events in time can be accounted for by the relation between the currently ongoing perceptual moment, and a rudimentary memory of the perceptual moment that preceded (Evans 2002: 22). The memory relating the two perceptual moments provides the experience of an interval in between the two, and thus, the conceptualization of two discrete moments. The awareness of either a dissimilarity or lack of dissimilarity between the current perceptual moment (what is being perceived), and the one that came before (what is represented in memory), is the basis of the experience of duration. Evans suggests that “(…) the succession between a perceptual moment held in memory and the current perceptual moment giving rise to the experience of duration constitutes (…) a relation which forms the basic unit of temporal experience” (2002: 22). Additionally, the conceptual integration of the succession of perceptual moments, the continually updated memory of past perceptual moments, and the diffuse array of sensory information received in the perception of the environment, gives rise to the fundamental perception of an “event” (2002: 24 et passim). In their discussion of conceptual models of time, Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 138-169) assert that time, rather than existing objectively in the world as a thing-in-itself, is defined by metonymy: “(…) successive iterations of a type of events stand for intervals of time” (1999: 138). The conceptualized magnitude of duration of an event, such as the movement of the hands of the clock, the change of day into night, etc., along with its “comparison” against the stored knowledge of the length of duration of other recurring events, is what constitutes the conceptualized magnitude of “time.” For example, the assertion that an event takes “two seconds” is reflective of the conceptualization of the event as compared against the cultural model of some recurring events in the world, such as the movement of the hands of the clock that is taken to be “one second” (see section 2.4.2 below for a conceptual blending account of these conceptualizations) These judgments depend on conceptual models which are culturally entrenched, and are reinforced by material anchors, such as the clocks themselves. The conceptualization of the magnitude of duration can vary in different circumstances. For instance, Evans, reviewing the findings of the psychologists Robert Ornstein and Michael Flaherty, describes the two widely reported judgments of the “speed” of duration, namely “protracted duration” and “temporal compression” (2003: 3-4). “Protracted duration” refers to experiencing time as passing “more slowly,” and it occurs when “(…) the density of conscious information processing is high” (Flaherty 1999, qtd. in Evans 2003: 4). This happens, for example, in emotionally charged situations, such as incidents of violence, where the experiencer’s attention level is extremely high. “Temporal compression,” on the other hand, is experienced when “the density of conscious information processing is low” (ibid.). This experience occurs, for example, when the conceptualizer is engaged in familiar, routine activities, which require little conscious attention. Citing the two ways of conceptualizing duration as evidence, Evans asserts that “(…) it is how we interact with and attend to a particular event, rather than any ‘objective’ temporal properties associated with an event which gives rise to our experience of duration” (2003: 3). 1.2.2. The basic metaphorical models of TIMEThis section will provide an overview of the basic conventional metaphors of TIME, based mainly on the account of conceptual models of TIME provided in Lakoff and Johnson 1999 (137-169).1.2.2.1. The TIME ORIENTATION metaphorAnalyzing the basic properties of the conceptual models of time in the English-speaking culture, Lakoff and Johnson state that, as the conceptualization of time originates from the conceptualization of regularly recurring events, the basic literal properties of time are the basic literal properties of events (1999: 138). This finding can be accounted for by the Invariance Principle, by which the topology of the source domain (here, EVENTS) is preserved in the mapping, as long as it does not violate the image-schematic structure of the target domain (here, TIME). Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 138) list the basic properties of time and the basic properties of events, which are:Time is directional and irreversible because events are directional and irreversible; events cannot “unhappen.” Time is continuous because we experience events as continuous. Time is segmentable because periodic events have beginnings and ends. Time is measured because iterations of events can be measured. Following Lakoff and Johnson, I will begin the discussion of the prevalent basic conceptual metaphors of time in the English-speaking culture with the TIME ORIENTATION metaphor. The TIME ORIENTATION metaphor is reflective of the basic conceptualization of time, present in all cultures of the world (see Radden 2003), namely SPATIAL TIME. Although there are areas in the human brain that have been found to be responsible for the detection of motion, there are no structures evolved for the perception of “time.” Unlike in physics, for the human mind motion seems to be a more fundamental concept than time. The TIME ORIENTATION metaphor is a basic cross-domain mapping which uses spatial and motional concepts as the source domain in conceptualizing the domain of TIME. In this mapping, there is a spatial configuration with an OBSERVER, localized at the PRESENT. The space in front of the OBSERVER is the FUTURE, and the space behind is the PAST. This can be represented in the following way:

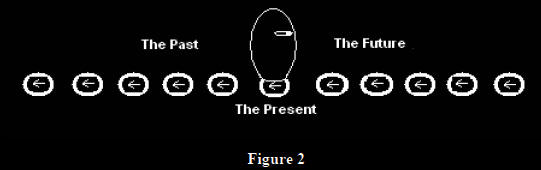

Linguistic expressions underpinned by this conceptual metaphor (quoted in Lakoff and Johnson 1999) include “That is now behind us,” and “He has a great future in front of him” (140). Lakoff and Johnson stress that “time orientation is cognitively separate from other aspects of time” (140). They assert that this metaphorical model does not specify the OBSERVER’s movement in time, but merely states the OBSERVER’s orientation. 1.2.2.2. The MOVING TIME metaphorsThere are two other basic conceptual metaphors that specify the OBSERVER’s MOVEMENT IN TIME, namely, the MOVING TIME metaphor and the MOVING OBSERVER. The former is described as follows (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 141):There is a lone, stationary observer facing in a fixed direction. There is an indefinitely long sequence of objects moving past the observer from front to back. The moving objects are conceptualized as having fronts in their direction of motion. Lakoff and Johnson specify the conceptual mappings in the structure of the MOVING TIME metaphor in the following way: Objects ���� Times The Motion of Objects past The Observer ���� The “Passage” of Time (1999: 141) This mapping is activated simultaneously with the TIME ORIENTATION metaphor, yielding the additional specification that the location of the stationary OBSERVER is the PRESENT, the space in front of the OBSERVER is the FUTURE, and the space behind is the PAST. Thus, TIMES move from the FUTURE, through the PRESENT, and into the PAST. The location of the PRESENT TIME is the location of the OBSERVER. Lakoff and Johnson provide a selection of linguistic examples of the MOVING TIME metaphor: The time will come when there are no more typewriters. The time has long since gone when you could mail a letter for three cents. The time for action has arrived. The deadline is approaching. The time to start thinking about irreversible environment decay is here. Thanksgiving is coming up on us. The summer just zoomed by. Time is flying by. The time for end-of-summer sales has passed. (1999: 143). The examples quoted above demonstrate how the use of spatial vocabulary is extended to yield temporal uses, as conditioned by the mapping of the structure of the domain of MOVEMENT IN SPACE into the target domain of TIME. Additionally, due to the Invariance Principle, certain crucial inferences entailed by the structure of the schema of MOVEMENT IN SPACE are inherited in the mapping. Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 142) point out that the fact that there is only one OBSERVER in the mapping conditions the inference that there is only one PRESENT TIME (because in the domain of SPACE, a single element can only be located in a single location). Since in the source domain of SPACE, the OBJECTS all move in the same direction, all the TIMES move in the same direction. Finally, as conventionally an OBJECT moving in space will be conceptualized as having a front-back orientation, with the front in its direction of motion (see Lakoff and Johnson 1980: 42), the inference for the domain of TIME in the MOVING TIME metaphor is that all TIMES face in their direction of motion. Lakoff and Johnson add further inferences that hold by virtue of the fact that in the cross-domain mapping, the domain of TIME is structured by the domain of SPACE (1999: 142). They point out that the OBJECTS in the source domain of SPACE, as the TIMES in the target domain, form a sequence. This conditions such inferences as, for example, if OBJECT 1 is behind OBJECT 2 as related to the OBSERVER, TIME 2 is in the FUTURE relative to TIME 1, and TIME 2 is in the PAST relative to TIME 1. Additionally, Radden (2003) points out that “(…) another way of viewing sequences of time is having them bounded at one end” (234) There are two viewing arrangements possible here. In one, “(…) the observer [is] positioned outside the sequence of time units.” The other has the observer “(…) included in the sequence of time units” (ibid.: 234). The former variety is activated by the English expressions like last week, last month, or last year. These expressions prompt the conceptualization of a sequence of time units, based on the cultural model of the calendar, in which the last element is positioned behind the OBSERVER. For example, if today is Wednesday, March 10, the expression “last week” will be read as “the week from Monday March 1 to Sunday March 7.” Alternatively, expressions like “the last week” or “the last month” prompt a conceptualization of a sequence of units of time (roughly seven days and roughly thirty days, respectively) which goes back from and includes the present (and hence, the observer). For example, if today is Wednesday, March 10, the expression “the last week” will be read as “roughly, the period of time between the moment of speaking and around seven days back,” i.e. approximately the time between now and March 3. The MOVING TIME metaphor can be represented in the following way:

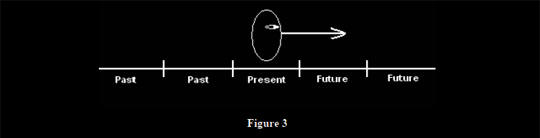

This metaphorical mapping is what provides the conceptual models that are activated in the comprehension of linguistic expressions such as the summer is coming, the exam is getting closer, I was just watching the days passing me by, that day is long gone, etc. Of course, this mapping can be observed in extra-linguistic behavior as well. As stressed by Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 144), it is common for speakers to point behind while uttering sentences like “that was in our past,” and to point ahead while uttering sentences like “it will come in our future.” Interestingly, Radden points out that “In English, time may be seen as flowing down from the earlier time into the present” (2003: 228). This conceptualization is evidenced by linguistic examples such as “These stories have been passed down from generation to generation,” or “This tradition has lasted down to the present day” (ibid.). Additionally, Radden suggests that for future time, English uses a conceptual model in which the OBSERVER (and hence, the PRESENT, where the OBSERVER is located) is positioned above the PAST and the FUTURE (ibid.: 228). FUTURE TIMES come up, and PAST TIMES go down. The examples Radden provides are “The new year is coming up” and “This year went down in family history” (228). As evidence for the cross-domain mapping of the MOVING TIME metaphor, apart from the inference patterns described above, Lakoff and Johnson cite examples of polysemous lexical items and poetic expressions (1999: 144). George Lakoff stresses that “[a conceptual metaphor] sanctions the use of source domain language and inference patterns for target domain concepts” (1992). Accordingly, the use of the domain of MOVEMENT IN SPACE in the structuring of the domain of TIME will sanction the temporal-reference use of certain lexical items, such as “before, after, behind, precede, follow, come, arrive, approach,” etc. The use of these lexemes will be grammatical in both spatial and temporal senses, and the temporal senses will be bound by the inference patters available in the domain of SPACE. David Lee states that Sentences will be maximally natural if the meanings they express correspond to natural ways of conceptualizing the relevant situation. Conversely, they will exhibit various degrees of unnaturalness to the extent that this correspondence does not hold. (2001: 77) Thus, a sentence like “Yesterday will not come before tomorrow” will strike the reader as ungrammatical, or incomprehensible without any additional context. Violating the inference patterns available in the domain of MOVEMENT IN SPACE, the sentence does not provide cues for a conceptualization based on the structure of the “natural,” conventional conceptual model of MOVEMENT IN TIME. 1.2.2.3. The metaphor TIME IS A CHANGERVery often, if an element is seen as usually occurring together with an event, that element will be conceptualized as a property, or even cause of the event. For example, if I am a singer, and my friend Mary has been in the audience a few times when my microphone went down in the middle of the performance, when that happens again I will get mad at Mary and call her a “jinx.” The lexeme “jinx” is used to refer to a person or thing that “brings bad luck,” or, in other words, is perceived as being the agent that caused an unfavorable (accidental) occurrence. Lakoff and Turner (1989) provide a discussion of this very interesting folk theory of causation (37 et passim). This metaphorical mapping in question is referred to as EVENTS ARE ACTIONS.Lakoff and Turner note that this conceptual metaphor is activated when “(…) we ascribe the occurrence of a particular event to a nonincidental property of something indispensably involved in the event” (ibid.: 37). In other words, this mapping creates an AGENT slot in the structure of the schematic representation of the event in question. Certain events, like aging, have no easily discernible cause. However, all the perceived changes that these events have consisted in occur in time. Thus, TIME is often what fills the AGENT slot in the conceptualization of the cause of an event through the mapping EVENTS ARE ACTIONS. This mapping leads to the creation of linguistic expressions such as “time-defying cream” or “he has aged.” This common conceptual metaphor is referred to as TIME IS A CHANGER (see Lakoff and Turner 1989: 37 et passim). TIME IS A CHANGER can be seen as a special case of the basic metaphor TIME IS MOVING. In the latter, TIME is conceptualized as an entity having an existence on its own, separate from events (see Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 156-158). This entity, conceptualized as the cause of the perceived change, fills the AGENT slot in the EVENTS ARE ACTIONS metaphor. There are many special cases of the TIME IS A CHANGER metaphor, which specify the kind of agent TIME is conceptualized as. They include: - TIME IS A DESTROYER (“Time has eradicated his beauty”) - TIME IS A DEVOURER (“Finance, like time, devours its own children.” – Honore de Balzac) - TIME IS A HEALER (“Time heals all wounds”) - TIME IS A PURSUER (“But at my back I always hear / Time’s wingéd chariot hurrying near.” Andrew Marvell, “To His Coy Mistress”) - TIME IS A THIEF (“Not to understand a treasure's worth / Till time has stol'n away the slighted good (…)” William Cowper) Our folk theories of the world hold no explanation of the causes of certain (often tragic) events, but these events always occur in time. Therefore, the TIME IS A CHANGER metaphor is commonly used to provide an explanation of a perceived change, with no other explanation readily available. The cultural existence of this conceptual metaphor can be observed not only in literary texts, but also in conventional expressions, like proverbs. For a discussion of examples of how the conventional conceptual metaphor TIME IS A CHANGER and its special cases provide structure for certain novel and conventional uses of language, see Lakoff and Turner (1989: 40-43 et passim). 1.2.2.4. The TIME IS SUBSTANCE metaphorIn a variation of the MOVING TIME metaphor discussed in section 1.2.2.2 above, in place of the sequence of TIMES, conceptualized as discrete objects, time is conceptualized as a flowing substance (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 144). This change of construal is reflective of the mental operation referred to as the multiplicity-to-mass image-schema transformation (see Lakoff 1987: 428-429 and 440-444). If a multiplex entity is perceived from a distance, it will be conceptualized as a mass. Applied to the conceptualization of time, this organizing principle of perception provides the construal of time as substance that can be measured, so that one can speak of a lot of time, less time, etc. Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 145) describe how the conventional knowledge of substances, involved in the mapping TIME IS SUBSTANCE by virtue of the Invariance Principle, leads to the formation of certain inferences in the domain of TIME. These are:• A small amount of substance added to a large amount of substance yields a large amount. ���� A “small” duration of time added to a “large” duration yields a “large” duration. • If Amount A of a substance is bigger than Amount B of that substance and Amount B is bigger than Amount C, then Amount A is bigger than Amount C. ���� If Duration A of time is greater that Duration B of time and Duration B is greater than Duration C, then Duration A is greater than Duration C. The conceptual metaphor referred to as TIME IS SUBSTANCE has two important special cases, namely, TIME IS A (FLOWING) LIQUID and TIME IS A RESOURCE. The former is an elaboration of the generic mapping TIME IS A SUBSTANCE, wherein the PASSAGE OF TIME is conceptualized as the flow of a liquid. This mapping provides the conceptual substrate activated by expressions such as “time flows fast when you’re having fun,” or by the title of an avant-garde “surf movie,” Liquid time (Example 3). The most readily culturally available conventional image9 of a linear body of water in constant unidirectional motion is A RIVER. Unsurprisingly, one special case of the conceptual metaphor TIME IS A (FLOWING) LIQUID is the mapping TIME IS A RIVER. This mapping can be seen at work in the following quotation from an article in The New York Times: “time ebbs and flows in a sluggish tide (…)” (Example 4). Another interesting example of how this mapping functions in thought is “The Time River Theory” developed by Goro Adachi (Example 5). In the words of its creator, the Time River Theory “[is about a] grand system of literal ‘rivers of time’ flowing on our planet, created by some mysterious, higher intelligence” (Example 5). The other special case of the TIME IS A SUBSTANCE metaphor is the cross-domain mapping named TIME IS A RESOURCE. In this metaphor, what maps onto the SUBSTANCE slot is the culturally entrenched RESOURCE schema. By virtue of this structure-mapping, the rich structure of elements and relations in the RESOURCE schema is mapped into the structure of TIME, providing the conceptual apparatus that enables the comprehension of such expressions as “I have no time; we’re running out of time; we have all the time in the world; time is precious,” etc. In a special case of the conceptual metaphor TIME IS A RESOURCE, the RESOURCE slot is filled with a salient member of the cultural model of RESOURCE, yielding the metaphor referred to as TIME AS MONEY. This mapping is strongly reinforced in the English-speaking culture (for example, by the practice of remunerating workers on the basis of how much time they have spent performing their duties). For a detailed discussion of the metaphor TIME IS A RESOURCE and the special case TIME AS MONEY, see Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 161-166. 1.2.2.5. The MOVING OBSERVER or TIME’S LANDSCAPE metaphorIn the basic conceptual metaphor referred to as the MOVING OBSERVER or TIME’S LANDSCAPE, the metaphorical OBSERVER is not stationary, but instead moves along a path. The locations on the OBSERVER’s path are TIMES, and the OBSERVER’s location is always the PRESENT (in other words, when a metaphorical location has been traversed, it comes to be conceptualized as PAST, while the OBSERVER’s current location becomes THE PRESENT). This can be represented in the following way: