Making Anti-Gravity

The key to antigravity was found by a Dutch

physicist, Hendrik Casimir, as long ago as 1948. Casimir, who

was born in The Hague in 1909, worked from 1942 onwards in the

research laboratories of the electrical giant Philips, and it

was while working there that he suggested what became known as

the Casimir effect.

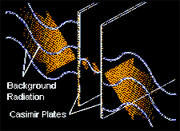

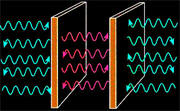

Among the particles popping in and out of existence in the quantum vacuum there will be many photons, the particles which carry the electromagnetic force, some of which are the particles of light. Indeed, it is particularly easy for the vacuum to produce virtual photons, partly because a photon is its own antiparticle, and partly because photons have no "rest mass" to worry about, so all the energy that has to be borrowed from quantum uncertainty is the energy of the wave associated with the particular photon. Photons with different energies are associated with electromagnetic waves of different wavelengths, with shorter wavelengths corresponding to greater energy; so another way to think of this electromagnetic aspect of the quantum vacuum is that empty space is filled with an ephemeral sea of electromagnetic waves, with all wavelengths represented. This irreducible vacuum activity gives the vacuum an energy, but this energy is the same everywhere, and so it cannot be detected or used. Energy can only be used to do work, and thereby make its presence known, if there is a difference in energy from one place to another.

The allowed vibrations are the fundamental note for a particular length of string, and its harmonics, or overtones. In the same way, only certain wavelengths of radiation can fit into the gap between the two plates of a Casimir experiment. In particular, no photon corresponding to a wavelength greater than the separation between the plates can fit in to the gap. This means that some of the activity of the vacuum is suppressed in the gap between the plates, while the usual activity goes on outside. The result is that in each cubic centimeter of space there are fewer virtual photons bouncing around between the plates than there are outside, and so the plates feel a force pushing them together. It may sound bizarre, but it is real. Several experiments have been carried out to measure the strength of the Casimir force between two plates, using both flat and curved plates made of various kinds of material. The force has been measured for a range of plate gaps from 1.4 nanometers to 15 nanometers (one nanometer is one billionth of a meter) and exactly matches Casimir’s prediction. In a paper they published in 1987, Morris and Thorne drew attention to such possibilities, and also pointed out that even a straightforward electric or magnetic field threading the wormhole "is right on the borderline of being exotic; if its tension were infinitesimally larger . . . it would satisfy our wormhole-building needs." In the same paper, they concluded that "one should not blithely assume the impossibility of the exotic material that is required for the throat of a traversable wormhole." The two Caltech researchers make the important point that most physicists suffer a failure of imagination when it comes to considering the equations that describe matter and energy under conditions far more extreme than those we encounter here on Earth. They highlight this by the example of a course for beginners in general relativity, taught at Caltech in the autumn of 1985, after the first phase of work stimulated by Sagan’s enquiry, but before any of this was common knowledge, even among relativists. The students involved were not taught anything specific about wormholes, but they were taught to explore the physical meaning of spacetime metrics. In their exam, they were set a question which led them, step by step, through the mathematical description of the metric corresponding to a wormhole. "It was startling," said Morris and Thorne, "to see how hidebound were the students’ imaginations. Most could decipher detailed properties of the metric, but very few actually recognized that it represents a traversable wormhole connecting two different universes." For those with less hidebound imaginations, there are two remaining problems -- to find a way to make a wormhole large enough for people (and spaceships) to travel through, and to keep the exotic matter out of contact with any such spacefarers. Any prospect of building such a device is far beyond our present capabilities. But, as Morris and Thorne stress, it is not impossible and "we correspondingly cannot now rule out traversable wormholes." It seems to me that there’s an analogy here that sets the work of such dreamers as Thorne and Visser in a context that is both helpful and intriguing. Almost exactly 500 years ago, Leonardo da Vinci speculated about the possibility of flying machines. He designed both helicopters and aircraft with wings, and modern aeronautical engineers say that aircraft built to his designs probably could have flown if Leonardo had had modern engines with which to power them -- even though there was no way in which any engineer of his time could have constructed a powered flying machine capable of carrying a human up into the air. Leonardo could not even dream about the possibilities of jet engines and routine passenger flights at supersonic speeds. Yet Concorde and the jumbo jets operate on the same basic physical principles as the flying machines he designed. In just half a millennium, all his wildest dreams have not only come true, but been surpassed. It might take even more than half a millennium for designs for a traversable wormhole to leave the drawing board; but the laws of physics say that it is possible -- and as Sagan speculates, something like it may already have been done by a civilization more advanced than our own. |